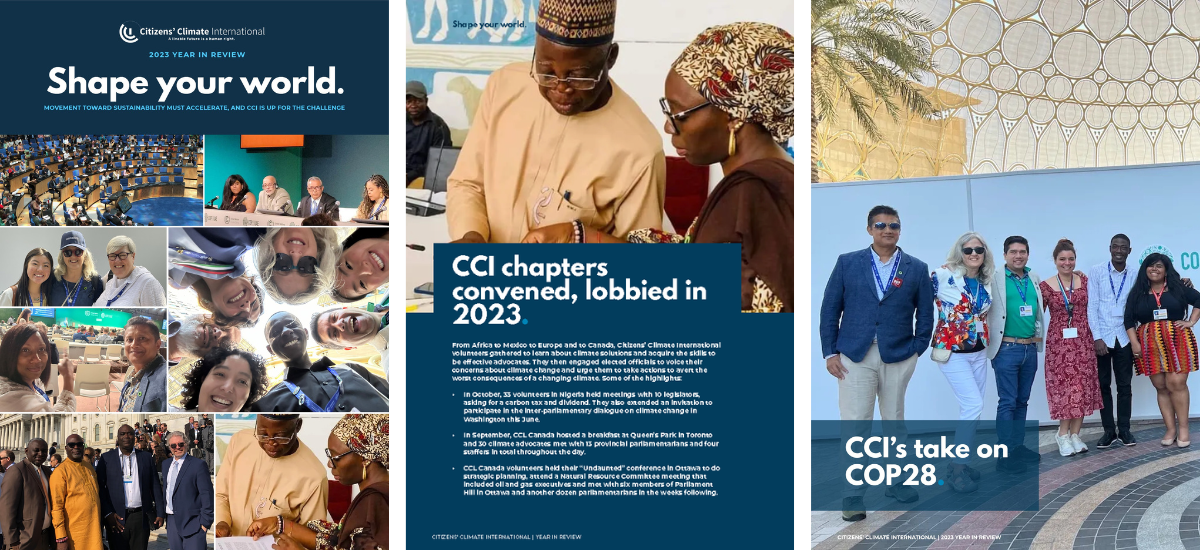

From May 31 through June 2, Citizens’ Climate International and the Fletcher School at Tufts University teamed up to host a series of trainings for diplomats and observers, ahead of the SB56 round of UNFCCC negotiations, which opened yesterday in Bonn, Germany. This three-part cycle of trainings aims to provide participants with the ability to enter the UNFCCC venue with the awareness, references, tools, and adaptive capacity required to keep their footing on uneven ground where new developments constantly threaten to disrupt well-founded strategic priorities.

Session 1: The Process

The United Nations Climate Change negotiating process, focused on implementation of the 1992 Framework Convention on Climate Change, involves 197 Parties (196 nations, plus the European Union). Parties negotiate toward legal decisions agreed by consensus, across dozens of active agenda items.

In the mid-year negotiations, the 197 Parties work toward consensus as two “subsidiary bodies” of the Convention: the Subsidiary Body for Implementation (SBI) and the Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice (SBSTA). During the annual “COP” meetings, the 197 Parties work as the Conference of the Parties to the Convention (COP), the SBI and SBSTA, and as the Meeting of the Parties to the Kyoto Protocol (CMP) and the Meeting of the Parties to the Paris Agreement (CMA).

The SB56 round of negotiations, which run from June 6 to June 16 in Bonn, must:

- begin to formally activate the outcomes of the Glasgow negotiations last November;

- make significant progress on mitigation, adaptation, finance, and many other areas of climate crisis response and mobilization; and

- set up the COP27 for major breakthroughs both in raising ambition and in delivering real-world transformative climate action.

In Session 1: The Process, we explored the structure of the negotiations, some of the key issues on the agenda in Bonn, and practical tools and strategies for gathering information, preparing to play a constructive role in the process, and good practices for sharing information with teammates and allies. We examined the role of Negotiator and the role of Observer, including how they can work together for better overall outcomes.

Rachel Kyte, Dean of the Fletcher School, reminded us that the UNFCCC process operates in concentric circles, with negotiators at the center, supported by experts and observers, as well as UN agencies, and with the press and general public, and other non-state actors, on the outside, affected by and needing to mobilize action. Dean Kyte also offered the following insights:

- Agility is a core skill for navigating the process.

- Experience shows that “small is mighty”, as some less developed countries have been instrumental in securing major breakthroughs and driving ambition.

- There is a need for enhanced research capabilities and upgraded participation of research institutions from the Global South.

- We need better, faster, and more detailed ways of tracking progress on net zero commitments.

Joe Robertson, Executive Director of Citizens’ Climate International, highlighted known good practices learned by the Citizens’ Climate delegation, which organizes CCI staff and stakeholder advocates and coordinators engaging in the UNFCCC process. Some practical considerations to keep in mind:

- The role of Accredited Observer is not a passive one; Observers help to ensure transparency and accountability, and also help to neutralize the politics that puts wealthy polluting interests between government action and climate change.

- It is most important to listen, learn, work to understand where good ideas fit, and to help others understand how the process comes together.

- Try to keep an evolving picture of the state of the overall process, and try to find constructive leverage points for consolidating that better picture.

- Everyone needs a little bit of that insight, and you can share such insights without disclosing information entrusted to you in confidence.

- The process can, and will, evolve without warning, according to machinations observers can neither see nor control.

Echoing Dean Kyte’s note on agility, he said every delegate—whether CSO, Party, UN Staff, or Media—needs to be ready to adjust their schedule and follow the often changing meeting schedule. Dynamic scheduling is a core skill every delegate—and their wider delegation—need to develop to be effective.

Most importantly, do not be intimidated by the complexity or unpredictability of the COP process. That is a natural byproduct of a process that brings together diplomats from 196 nations and observers from thousands of organizations, to have a focused discussion about the details of a 5 structured processes for implementing a treaty that mandates transformational action.

Session 2: The Stakes

Our second Pre-SB56 Climate Diplomacy Workshop looked at what science and experience tell us is at stake, depending on how the negotiations play out and how well nations, and their whole societies, follow through. The session opened with two revealing charts.

The first graphic showed the five future global heating scenarios produced by Working Group I of the IPCC in its report on the physical science basis, described by the United Nations Secretar-General as “code red for humanity”. The report found that only in the most ambitious scenario, with immediate, ongoing, and universal decarbonization, can we hold global heating to 1.5ºC or lower this century.

The second graphic (below) was the Whole-Earth Active Value Economy (WEAVE) knowledge graph, which mapped climate, water, and biodiversity impacts to a dozen other sustainability and resilience areas of concern. The knowledge graph suggests that a denser network of known knowledge connections in these areas amounts to enhanced resilience and adaptive capacity.

Specific resilience failures during the COVID pandemic shutdowns confirmed that at least in some cases, a thinner WEAVE knowledge graph correlated to gravely reduced adaptive capacity. Increasingly, we need to know which institutions, nations, regions, and sectors, are positioned to fare well in the climate resilience economy.

How resilient are we, and what tools can give us clear answers?

Cathy Orlando, CCI Program Director, highlighted the importance of civic engagement for alignment of science insights with local outcomes. As stakeholders become more engaged, policy becomes better informed about local experience and can better translate science insights into local opportunity, resilience, and sustainable prosperity.

She reported on the mobilization for economic transformation through bodies like the G7 and G20, in line with the rights and priorities of women, youth, indigenous peoples, and other stakeholders. Not only do these stakeholder groups now inform the leaders summits; they are asking for high ambition climate policy, including economy-wide carbon pricing.

Isatis Cintrón, CCI Latin America Coordinator spoke about the need for the SB56 to activate the Glasgow Work Programme on Action for Climate Empowerment, to have real-world effects that align policy with stakeholders’ experiences, with human rights, including the right to a livable and equitable future, and with participatory process for informing decision-makers and holding implementers accountable.

The right to participate, to be informed and to inform decision-makers, was cut out of the Glasgow Work Programme, she noted. This was partly owing to the unprecedented barriers between negotiators and observers, due to COVID safety measures. Not aligning climate policy and civic engagement with human rights reduces accountability, ambition, and follow-through. The SB56 Action Plan for implementing the Glasgow Work Programme must align with the human rights language cited in the Paris Agreemnet and the Glasgow Pact.

Karl Burkhart, Deputy Director of One Earth, brought vital insight into what science tells us about impacts on the natural world, the global safety net, and pathways to a climate resilient future with no more than 1.5ºC of global heating. Drawing on the IPCC Working Group III report on Mitigation, Karl cited urgent warnings about what is at stake:

- Increasing concern about acidification, desertification, depleting natural systems;

- Our global economy is highly vulnerable to shocks, which can emerge from convergence of nonlinear, compouding forces;

- Food security is becoming a global crisis and will be a major focus for COP27 in Egypt;

- We could lose as much as 8% of our global crop land;

- It’s hard to conceive of what that will mean, in terms of hunger and displacement.

Sharing the new One Earth reference model, Karl shared that it is possible to meet the 1.5ºC goal with $1.5 trillion invested annually. Realigning investments sooner rather than later can make this an affordable, mainstream, value-building proposition. We can meet the 1.5ºC target, but we must act quickly, across all sectors, and with a new understanding of the value nature contributes.

Quamrul Chowdhury, long-time lead negotiator for the Least Developed Countries and the G77, brought us many insights from the negotiations as such. He said the urgent priorities for Least Developed Countries at the SB56 include, but are not limited to:

- Defining the Global Goal on Adaptation

- Upgrading ambition and accelerating implementation – EVERY nation should revise upward NDCs and aim for net zero sooner

- Keeping 1.5C alive – with all that means for the viability of human societies and ecosystems across the world

- Significant improvements to and enhanced funding for capacity building

- Progress toward Loss and Damage financing – for both economic and non-economic losses

- Activating the climate capability of all nations and defending the climate rights of vulnerable communities in all nations

- Quadrupling finance for adaptation

- Mobilizing finance across sectors

- Investing to reduce vulnerability in the most affected communities and countries

The stakes are existential for vulnerable countries and communities, for biodiversity and ecosystems, for the security of food and water supplies. The stakes are heightened still further by the fact that the SB56 negotiations take place during a multidimensional global crisis requiring transformation of food, energy, and finance. Failure to properly address these short-term emergencies could put the SDGs and Paris goals out of reach.

Session 3: Navigating Complexity

Our third Pre-SB56 Climate Diplomacy Workshop featured detailed discussion with Dean Kyte and with Maghan Keita, Professor of History and Global Interdiscipilnary Studies at Villanova University and Board President for Citizens’ Climate International.

Dean Kyte opened the workshop with the heady observation that:

“We are facing the ultimate test of solidarity.”

She noted that this particular aspect of the climate challenge is regularly invoked by United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres. The operative question, she noted, is whether solidarity is within our capabilities.

Right now, the world faces multiple converging and compounding crises.

- Food insecurity is spreading rapidly, and could affect billions of people this year, if more is not done to address climate-related crop failure, trade blockages, and perverse incentives driving price spikes through commodity markets.

- The World Bank and International Monetary Fund are reporting that “60 percent of low-income countries are now at high risk of or already in debt distress, compared with fewer than 30 percent in 2015”.

- Unprecedented nature loss exacerbates the risks to everyday human security and environmental sustainability, and makes it harder to produce food sufficient to overcome natural and artificial food system failures.

The impact of the negotiations reach far beyond the scope and capacity of the negotiations. Real-world impacts are happening every day, and real-world capabilities to address climate-related challenges are almost entirely external to the process.

There is hope in the mainstreaming of climate priorities, including in risk analysis and regulatory action from finance regulatory agencies. Increasingly, we see “coalitions of the working” forming to mobilize resources, transform market dynamics, build guardrails and set the rules of the road. Meanwhile, policy is not moving as fast. Many countries have not fully confirmed their stated climate goals in national law.

In addition to the ambition gap (we need to set stronger targets) and the implementation gap (we need to do more to meet existing targets), climate crisis response is also constrained by a coherence gap: We need all areas of policy, investment, development, and innovation, to align with the highest ambition and most robust and persistent implementation.

Dr. Keita took participants through an inquiry into the reading of text, critical thinking, bodies of knowledge, and finding solidarity in facing complexity. While “knowledge is power”, he noted, the UNFCCC process must, by the nature of its mission, recognize and integrate numerous bodies of knowledge.

This includes the question of how national authorities and supranational decision spaces can access the knowledge of the public. How can experience at the human scale best inform high-level decision-making, and how does that knowledge translate into agency for activating climate action goals?

The text that needs reading is not limited to drafts on the table in the room. “Everything around us is text,” said Dr. Keita. Do we now how to read that text, to understand what is bubbling up, what emerges from experience at the human scale, and so what is most potentially transformational, because it is rooted there?

“Conscious and deliberate acts of critical thinking” are needed to navigate the dynamism, the shifting sands, the concentric circles, and the compouding risks and impacts that comprise the global climate negotiations. That critical thinking means listening not for ways to achieve one’s own predetermined goal, but for opportunities to form new alliances, make room within our own perspective for unfamiliar but possibly fruitful connections, and to get closer to an outcome reflective of practical solidarity.

Dr. Keita echoed Dean Kyte’s observation that “small is mighty”. The people in the outermost concentric circle have the practical virtue of being “voluminous”. Integrating their needs and priorities, their rights and capacities, allows for working at scale. Inclusion means more witnesses, higher stakes, higher ambition, and greater accountability.

Ultimately, this process must translate science insights into future experience. Conscious and deliberate acts of critical thinking, about the real-world ramifications of each alignment or misalignment, must be part of the calculus. It was observed that we must, sometimes, “slow down”—not to avoid moving foward, but to listen, learn, and improve this capability for work toward successful solidarity outcomes.

Recognizing the need to do this, while accelerating the pace of real-world climate crisis response, Dr. Keita closed the workshops by saying:

“We can slow down and still be moving at the speed of light.”

Takeaways

- The process is complex; get comfortable with that, and listen for opporutnities to build alliance across diverse perspectives.

- Value the constructive contributions of each type of participant, given the specific role they play as negotiators, stakeholder-observers, media, or UN staff.

- Learn the details of the formal Agendas, and plan to align your schedule with the language and timing built around them.

- The stakes of this process are existential for billions of people and most ecosystems on Earth; the challenge of high-ambition consensus is “the ultimate test of solidarity.”

- Addressing loss and damage is not a gift or a loss; it is a moral responsibility and a critical safeguard of every nation’s capacity for sustainable development.

- Converging and compounding global crises cannot be made easier by ignoring the climate challenge; reducing climate risk is vital for crisis resolution.

- The negotiations should improve global cooperative performance on the 10 Recommendations from the Stockholm+50 Conference.

- Trust, accountability, and mutual investment in higher ambition are all enhanced by inclusion, cooperation, and follow-through.

Going forward

- Ongoing Discussion – We will be following up on the details of the three workshops and the overtime discussions and will provide additional materials through the CCI Momentum digital platform.

- Office Hours – We will hold virtual “office hours” sessions during the SB56, with interested workshop participants, 30 minute discussion sessions during the 1st and 2nd weeks, inside the CCI Momentum digital platform.

- Debrief – We will hold a formal debriefing session for instructors, partners, and team members, toward the end of June, to plan the details of the next round of workshops.

- Pre-COP27 – We have also begun expanding the scope of the future workshops, as new requests have come in for online and hybrid events in the run-up to the COP27.

- Learn more – To request further information about the pre-COP27 cycle of Climate Diplomacy Workshops, please reach out to cop27(at)citizensclimateintl(dot)org