Reinvent Prosperity, Include Everyone, Secure the Future

Throughout 2020, citizen stakeholders and advocates from the Citizens’ Climate International community shared their experiences of COVID risk, adversity, and resilience. This allowed an examination of COVID risk and recovery questions, in terms of day-to-day experience at the human scale.

In light of the urgent need to act to avert catastrophic climate disruption and to align economic recovery efforts with that global project, we combined these stakeholder inputs with resilience intelligence insights to formulate the Principles for Reinventing Prosperity—an approach to building back better from COVID, to enhance the everyday wellbeing of people and planet.

We listed 3 areas of action under each of the principles, not as a definitive list, but as a starting point for quick action toward green and inclusive recovery:

Principle 1: We are all future-builders.

- Value the role of every person in rebuilding for a better future.

- Create participatory policy-design processes and public accountability.

- Mobilize capabilities at the human scale, to expand the agency of individuals and communities.

Principle 2: Health is a fabric of wellbeing and value.

- Study health impacts at all scales.

- Develop clear, context-specific metrics revealing the health-building or health-eroding value of both existing and emerging technologies and practices.

- Put health first—rewarding those that reduce harm and maximize wellbeing and resilience.

Principle 3: Resilience is a baseline imperative.

- Eliminate pollution.

- Map the action steps to better futures.

- Leverage sustainable food and land use strategies—as well as green infrastructure and ecosystem services—to minimize risks.

Principle 4: Leave no one behind.

- Honor the Right to Know.

- Redirect finance to empower communities and enhance agency.

- Let people lead, prioritizing participation, locally rooted solutions, and sustainable shared prosperity.

Principle 5: Design to transcend crisis.

- Price pollution and expand incomes.

- Reinvent food systems.

- Redesign infrastructure, trade, and financial systems to align with and build on the resilience value of persistent progress toward all 17 of the Sustainable Development Goals.

Principle 6: Maximize integrative value creation.

- Collaborate across watersheds.

- Establish resilience value.

- Prioritize Nature-positive investments in all areas.

1 year on from the release of the Principles, we now examine the state of the world, in light of those 18 areas of action, and specifically in terms of:

- addressing hunger and food insecurity;

- what science tells us about the global climate resilience project;

- COVID trends and impacts globally;

- COVID recovery in light of macrocritical resilience factors;

- disruptive economic and technological trends;

- rooted, distributed systems to operationalize major commitments.

Addressing hunger and food insecurity

UN Sustainable Development Goal 2 seeks to end hunger in all its forms by 2030, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture. While this goal was introduced almost 5 years ago, 842 million people are still estimated to be suffering from chronic hunger, while malnutrition is still the single largest contributor to disease in the world. According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the costs of undernutrition and micronutrient deficiencies are estimated at 2-3% of global GDP, adding up to $1.4 trillion to $2.1 trillion per year.

Addressing hunger and food insecurity is not just an issue in developing countries, but also in developed countries like the US. The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly known as food stamps) is one of the most important anti-hunger programs in the US. In fiscal year 2019, SNAP served an average of 35.7 million people per month, or 11% of Americans. The percent of residents receiving SNAP benefits ranged from 19.8% in New Mexico to 4.2% in Wyoming.

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to severe and widespread increases in food insecurity, affecting vulnerable households in almost every country, with impacts to continue for years to come. According to FAO’s 2021 report titled The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World, SDG 2 (Zero hunger by 2030) will be missed by a margin of nearly 660 million people – 30 million more people than in a scenario in which the pandemic had not occurred.

The pandemic has also exposed vulnerabilities in global food systems which could be further upended by the climate crises. A shortage of workers around the world, driven by the pandemic, is already shaking up the food supply chain. As Bloomberg reports:

“In Vietnam, the army is assisting with the rice harvest. In the UK, farmers are dumping milk because there are no truckers to collect. Brazil’s Robusta coffee beans took 120 days to reap this year, rather than the usual 90. And American meatpackers are trying to lure new employees with Apple Watches while fast-food chains raise the price of burgers and burritos.”

While companies are realizing the need for an agile food system that is flexible and adaptive to unexpected disruptions, the mismatch of supply and demand, amid unprecedented and compounding risks, makes adaptive management decisions far more challenging. Operating within, and in spite of, uncertainty will likely be the rule. A transformation in practices to allow routine activities to build resilience is where there is the greatest potential for new value creation.

With the global population rising to 10 billion by 2050, the EAT-Lancet Commission report clearly outlines that to feed the growing world population, transformation of eating habits, improvements in food production and reductions in food waste will be critical. If we don’t reinvent the food systems, supply chain disruptions like those brought about by COVID-19 will be just a precursor for a multiple breadbasket failure that will be driven largely by climate risks and resulting cascade effects. We need to leverage sustainable food and land use strategies—as well as green infrastructure and ecosystem services—to minimize risks.

What science tells us about the global climate resilience project

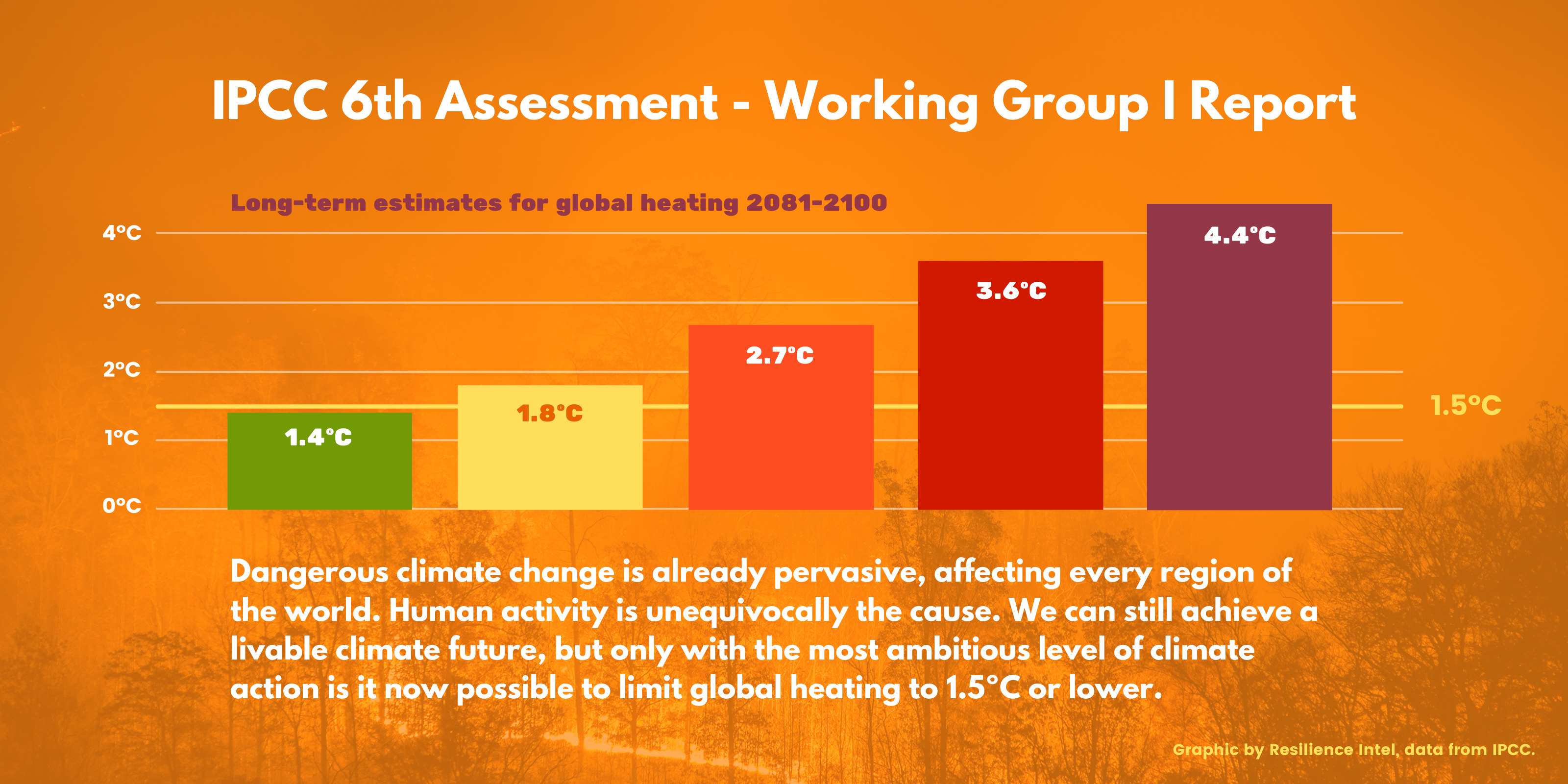

The August 2021 report of IPCC Working Group 1, on the Physical Science Basis for the 6th Assessment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) examined the entire history of climate-related scientific evidence, and projected 5 future scenarios. The science shows that only in the most ambitious scenario—with universal, immediate, intensifying, and sustained action to reduce and eliminate carbon pollution—will we manage to limit global warming to 1.5ºC, which is necessary to avoid dangerous climate destabilization.

The report finds that human influence has warmed the climate at a rate that is unprecedented in at least the last 2,000 years. Strong, rapid, and sustained emissions reductions are needed to reach net zero by 2050 and eliminate pollution.

The report finds that human influence has warmed the climate at a rate that is unprecedented in at least the last 2,000 years. Strong, rapid, and sustained emissions reductions are needed to reach net zero by 2050 and eliminate pollution.

To reach that goal, President Biden announced during the 2021 Leaders’ Climate Summit a target to achieve 50-52% reduction from 2005 levels in economy-wide net GHG pollution by 2030. Two of the major elements of this national decarbonization strategy are a transformational infrastructure upgrade and the aim to reach 100% carbon pollution free electricity by 2035.

If the US achieves this, it would be a huge boost to the global climate resilience project, not just as an example, but as an engine for investment and innovation. Political divisions and lack of public clarity about the balance of cost and risk. Making such big investments in climate resilient economies will give the American people a better, more livable economy; a significant cross-section of the political universe wrongly believes the opposite.

Across the Atlantic, the European Commission released its Fit for 55 package a few months ago to sharply reduce GHG emissions, across the 27 European Union member states, by 55% by 2030. The legislative and policy package includes proposals like integration of new sectors into the EU’s emissions trading system, new CO2 standards for cars, new infrastructure for clean transport, measures to prevent carbon leakage, etc.

The problem we face at the moment is that, even with all of these plans and pledges, the majority of spending and investment globally is still tied to pollution. The planned EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism is intended to address this, to reduce “leakage” of carbon pollution to jurisdictions without similar goals or carbon prices.

The Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ) was launched in April 2021 to assemble, align, and detail major financial commitments to mainstream climate finance. GFANZ, which is chaired by Mark Carney, will work to mobilize the trillions of dollars necessary to build a global zero emissions economy and deliver goals of the Paris Agreement while prioritizing nature-positive investments. Over 450+ financial firms responsible for assets in excess of $130 trillion are now part of the Alliance to align capital with science-based net-zero ambitions.

On Finance Day at COP26, an open plenary session examined the potential of advanced Earth observation systems supported by international cooperation.

Science-based targets, and the pathways to meeting them, must align with overall reduction of global emissions by 50% by 2030. Institutional changes are needed in the way we look at climate finance, both to bring climate risk mitigation and solutions into everyday activity and to make sure we deliver value-building climate finance to marginalized communities.

Unless we can enhance the agency of those left out of today’s extractive financial and industrial systems, we will not be able to align future profit with sustainable, inclusive, resilience-building value-creation. And the science is telling us that if we are to have prosperity, it must be sustainable, inclusive, and resilience-building.

COVID trends and impacts globally

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted institutional and commercial arrangements and distribution systems, reducing incomes and exacerbating income inequality across the world. Interactions between people at all scales—local, national, and global—have been altered in ways that will last for years. The Centre for Global Development cites these trends:

- a global economy deep in crisis, with recovery projected to be historically unequal (one example: the pandemic has pushed Africa into its first recession in 25 years);

- steep decline in global trade and financial flows to developing countries;

- reversed progress in global poverty reduction and human development;

- amplified inequalities, including in gender and digital accessibility; and

- strengthened forces of rivalry, anti-globalization, nationalism, and vaccine apartheid.

All of these negative trends are structural threats to the global economy, and to international peace and security. All of these trends need to be corrected before we can say for certain that climate resilience plans, and the needed transformation at all levels, are moving fast enough and reaching enough people to avoid out-of-control climate emergency.

Even as the COP26 opens in Glasgow, vaccinations rates are still dangerously low in most countries, and a new mutation of the Delta Variant of the SARS-CoV-2 virus is beginning to gain ground. Even if COVID were not more dangerous than influenza—and so far it has been far more dangerous—it cannot be contained in a state of manageable endemicity if its mutations begin to outpace vaccine development. So far, the most effective vaccines appear to retain significant efficacy against emerging variants, but that is expected not to hold, if major outbreaks keep creating hotbeds of infection that generate further mutations.

Health is affected not only by the narrow slice of professional services or areas of scientific inquiry we define as health-related. Health is affected by countless factors both immediately connected to our wellbeing and also those connected through complex and layered interactions.

We have seen a significant increase in multidisciplinary discussion about mitigation of global threats, like COVID, climate, and inequality. That is one of the signs that we are learning from the pandemic and may be positioned to make the right kind of choices in the short term to reduce future risk of pandemic spillovers.

But, we haven’t begun to reverse our destructive treatment of natural systems, which is the critical step required for halting the accelerating rate of pathogen spillovers. We need to focus on the big challenges in front of us, but we also need to widen the angle of the One Health lens, so our resilience planning is as robust, adaptive, innovative, and transformational as possible.

COVID recovery in light of macrocritical resilience factors

The Development Committee Communiqué issued during the Spring Meetings of the World Bank Group and the International Monetary Fund, in April this year, acknowledged the need for sustainable and inclusive recovery in light of the Covid-19 pandemic and the ongoing climate crises. Both these threats are interconnected: both crises affect the health, well-being, and livelihood of people worldwide, particularly vulnerable populations.

Increased climate investments are needed, with priorities including quality health care, nutrition, and education; social safety nets; digital and other innovative technologies; sustainable and quality infrastructure; access to energy; broader opportunities for women and girls; finance for SMEs and microenterprises. According to the ILO, the equivalent of an unprecedented 255 million jobs were lost as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, which led to a sharp increase in poverty and inequalities.

The differential impacts of the pandemic are likely to leave an enduring scar on the overall macroeconomic performance of economies. Even the wealthiest societies suffer significant opportunity cost due to the effects of deepening inequality. We are, as economists and decision-makers have observed in recent months, living beyond some of the core structural assumptions of mainstream economics.

In other words, we don’t know exactly what some of the current trends will resolve into, as everyday impacts of deep structural disruptions become foundational. Without comprehensive, concerted, and inclusive policy efforts, valuing the individual empowerment of everyone, there is a very real risk that the COVID-19 crisis will leave a legacy of deeper inequality and social injustice.

We need to redesign infrastructure, trade, and financial systems to align with and build on the resilience value of persistent progress towards all 17 of the Sustainable Development Goals. The SDGs are a “business plan for the world”, shaped around the core insight that working toward best-case outcomes is the most reasonable thing we can do. Innovation, empowerment, and righting injustice all mean we will induce and experience disruption.

We need to redesign infrastructure, trade, and financial systems to align with and build on the resilience value of persistent progress towards all 17 of the Sustainable Development Goals. The SDGs are a “business plan for the world”, shaped around the core insight that working toward best-case outcomes is the most reasonable thing we can do. Innovation, empowerment, and righting injustice all mean we will induce and experience disruption.

We need these disruptions to be good for people, good for the biosphere, and to create conditions for rewarding investments that do good beyond the balance sheet. The Good Food Finance Network is an example of this way of thinking. With tens of trillions of dollars being committed to sustainable outcomes, the GFFN is looking at the process of instrumentation—which tools, policies, and actions on the ground, will allow that money to do the good being promised.

Disruptive economic and technological trends

Over the past year, Covid-19 has magnified the need for structural and technological changes needed while creating disruptive economic trends. Governments around the world are embattled due to the rise of fiscal and political pressures while pushing the need for national self-sufficiency and resilience in the face of crises. The labor market has been changed forever with the rise of remote work options and the increased demand for service jobs.

While all these trends continue to solidify, significant technological changes are needed to drive climate ambition. As the IEA points out in its latest Net Zero by 2050 report, we need to achieve, besides other things:

- By 2030: universal energy access, all new buildings are zero-carbon-ready, phase out of unabated coal in advanced economies

- By 2035: no new sales of cars with internal combustion engines, overall net-zero emissions electricity in advanced economies

- By 2040: net-zero emissions electricity globally; phase out of all unabated coal and oil power plants, 50% of fuels used in aviation are low emissions

- By 2050: almost 70% of electricity generation globally from solar PV and wind; more than 85% of buildings are zero-carbon-ready

Beyond projects already committed as of 2021, IEA recommends that no new oil and gas fields should be approved for development and no new coal mines or mine extensions are required in its net zero pathway recommendation. Moving forward, the biggest areas of innovation will be advanced batteries, hydrogen electrolysers, and carbon capture and storage, which will be critical in solving the climate crises.

Artificial intelligence systems now make it possible to integrate diverse and disparate data platforms into complex, integrated, and evolving instruments for targeted ratings. Quantum computing could dramatically amplify this capability and create far more precise and adaptive data integration systems, by allowing the mapping of planetary-scale fluid dynamics and organic molecular processes.

There are practical, everyday implications to this level of disruptive data mapping. Interactions between industry, the atmosphere, soil ecology, food systems, watersheds, ocean health, and the climate, will be traced and valued. This is a light on the horizon, and should inform planning around complex emissions reduction pathways, realignment of public and private investment, and local economic development planning.

Rooted, distributed systems to operationalize major commitments

Power tends to operate by excluding some for the benefit of others. Economic, financial, and market “efficiency” has been treated as the degree to which overall costs to enterprise can be reduced. While that is one kind of efficiency, measuring it does not guarantee that negative external impacts will be avoided. In fact, this standard tends to incentivize activities that can achieve enterprise efficiency while pushing harm onto innocent outside parties.

In effect, this thinking is efficient for centralized power, and centralization of power, wealth, and capability, is one of the structural challenges to achieving generalized human wellbeing. The COVID pandemic emergency made clear that institutional arrangements, including business supply chains, that achieve efficiency in this way struggled to adapt.

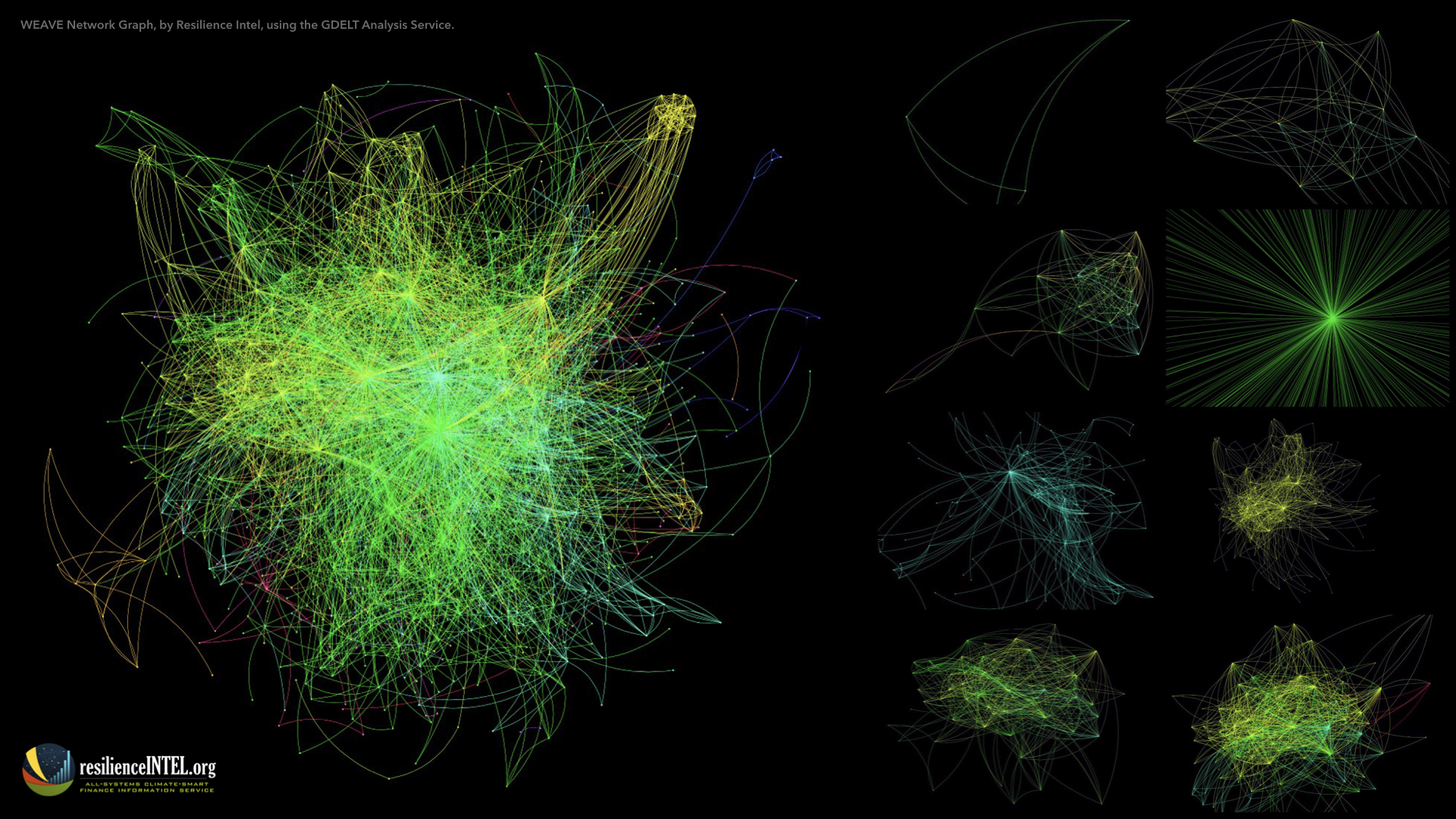

We share the WEAVE knowledge graph as often as we can. It shows that lower resilience knowledge leads to reduced adaptive capacity.

Major food industry actors, with highly centralized supply chains, were offered overwhelming public support, and special legal conditions under military orders, and still some failed to deliver their product to new locations. A major hunger crisis was avoided because of the adaptive capacity of decentralized networks of charitable institutions, community organizations, leveraging public support and helping people in need align with government assistance.

To overcome the crisis of converging sustainability deficits, we need more people to have greater agency—the ability, and the resources, to make smart choices and increase the overall resilience value available to others. Instead of de-risking investment by favoring the few with special legal treatment, we must design, learn to use, and activate cooperative de-risking strategies, in which stakeholders with widely varied interest, geography, and levels of affluence or influence, contribute to each other’s risk reduction.

Making such inclusive, empowering, distributed systems the norm is a critical piece of the puzzle for eliminating the incentive to pollute, or to externalize cost. Enhancing agency also means people need to be surrounded by better choices. You cannot choose better, if your menu of options are not in fact better.

With the major financial commitments being announced at COP26 in Glasgow, we have a chance to turn ideas into action, and for that action to create better, safer conditions for real human thriving. For that to happen, at the scale and speed required, huge investment portfolios—some larger than most countries’ whole economies—must put down roots in communities and let people conventionally left out of the system become agents of transformational innovation.

Are we reinventing prosperity?

Reviewing the 6 Principles, we take stock in a broad sense of whether we are starting the process of reinventing prosperity:

- Principle 1: We are all future-builders. Unfortunately, across most of the world, the individual everyday agency of most people has been reduced, as economic inequality has widened and trillions of dollars have been transferred to the wealthiest people. We are, however, beginning to see an increase in awareness about the importance of allowing local decision-making to be a mechanism for bringing resilience thinking to scale.

- Principle 2: Health is a fabric of wellbeing and value. The conversation among world leaders, global institutions, and across the private sector, about zoonotic disease risk (the risk of another, future COVID crisis) is opening up room for this discussion beyond the highly specialized networks where it was already happening. Our economies are not being adequately redesigned to avoid pollution and to foster health and wellbeing.

- Principle 3: Resilience is a baseline imperative. Major infrastructure initiatives, COVID recovery plans, sustainability-aligned finance commitments, are all sings of this awareness taking hold. We need to see more effective and widespread defense of the human rights implications of failing to build resilience, protect human health, or promote equality.

- Principle 4: Leave no one behind. Billions of people are being left behind, right now. From vaccine inequity to the high cost of capital for developing countries, global economic recovery is working through institutions that have not figured out how to succeed without sidelining the wellbeing, dignity, and agency of some people.

- Principle 5: Design to transcend crisis. We need institutions that are designed to operate in a world where we value every person and where we honor our role as stewards of any natural system we make use of. We need to promote technologies, business models, and community-level decision-making so we are less vulnerable to major shocks. Emerging from COVID safely and successfully will require creative future visioning.

- Principle 6: Maximize integrative value creation. $130 trillion aligning with science-based net-zero goals should jump start a push for integrative value creation—investment that aims to achieve multiple kinds of value added. We need to integrate Earth observations into financial decision-making, and we need to demand major resilience outcomes at the human scale.

COVID recovery investment is much dirtier than it should have been. Major supply chain disruptions can be traced, in part, to an unhealthy and illogical dependence on fuels whose prices don’t correspond to the persistently mounting costs they generate. In the first year since we released the Principles for Reinventing Prosperity, we have seen a major increase in discussion and commitment around sustainable planning and investment.

Now, we need to infuse that more inclusive, actively resilience-building mindset into everything we do.

This Resilience Intel Reinventing Prosperity report includes research and writing from Shantanu Agrawal—a former Resilience Intelligence Fellow.